Blog

Bridging the Gap: Using experimentation to unlock skills and talent

Lessons from the ‘Unlocking Innovative Potential’ experimentation programme and insights on what next

28 January 2026

The case for unlocking innovative potential is clear. The question for policymakers is how to respond.

Existing research has demonstrated the scale and dimension of the problem, with developed economies across the OECD losing necessary talent to fuel and shape R&D sectors ¹. We also know that if women, minoritised groups and people from low socio-economic families were to invent at the same rate as men from high-income families, the rate of innovation would increase substantially. What we don’t know is which of the many attempted solutions to reach, equip, and retain potential innovators should be scaled, or how to scale them.

This premise set the foundation for IGL’s Unlocking Innovative Potential (UIP) Experimentation Programme 2024-25. We partnered with organisations delivering promising programmes to test the feasibility of using experimentation to help them make more informed decisions about programme design and implementation, while also learning about wider policy application. In less than one year, we succeeded in bringing together researchers, policymakers and practitioners around this shared agenda – demonstrating the value of regular Community of Practice spaces to share policy ideas, emerging evidence and lessons learnt.

This blog summarises what we learnt about making experimentation happen on the ground, its inherent value to delivery teams and how we might go about scaling what we learnt in our small-scale pilots. We end by presenting our revised long-term approach to answer the most pressing policy questions: What policies to retain lost talent are most effective, what context-specific details influence their effectiveness, and which ought to be scaled?

Locating testable and policy-relevant ideas

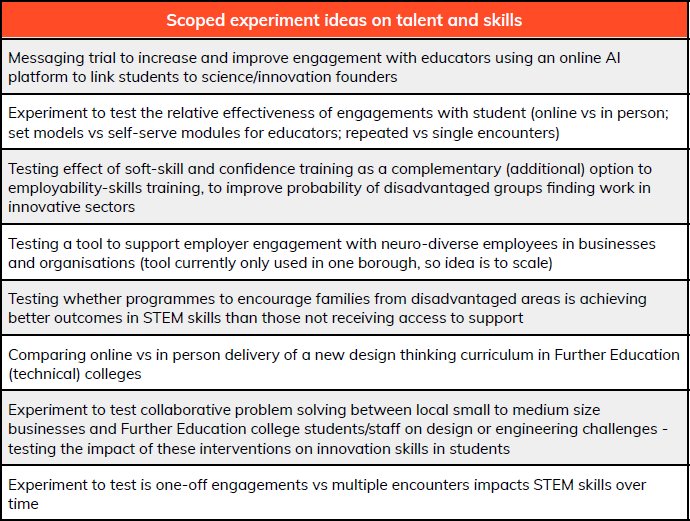

The delivery organisations that set out with us in 2024 were motivated by the prospect of harnessing evidence but were new to experimentation. Identifying the necessary functions and conditions to action experimentation required careful facilitation from our side. We began by casting the net as wide as possible, seeking ‘good problems’ to solve. In collaboration with our partners, we took these ideas through an iterative filtering process based on their potential to fill critical evidence gaps for the organisation, and thereby improve decision-making. This first gathering step led to a total of eleven experiment ideas that are listed below.

Scoping is the first step in any experimentation process, but even well-defined problems do not always fit into testable hypotheses suitable for an experiment. We faced a rigid timeline and resource constraints that further limited which ideas were viable. To address this, IGL supported partners to identify promising experiments using the PICO approach. All ideas needed to have a clear Population, Intervention, Comparison (or Control), and Outcome.

Our ambition was to identify ideas that could eventually scale into larger field experiments. The scoping process revealed that few interventions were immediately ready for this step but we were able to identify several cases where this would be possible.

Our final filter was to consider the broader policy relevance of learning about the impact of the intervention or how it could be best delivered.

The portfolio of experiment ideas that emerged sit within two broad categories:

1. Unlocking talent and skills

Improving the pool of R&D talent is a high priority for UK policymakers. Unlocking this potential involves improving skills, confidence, and access to opportunities for underrepresented groups. During the scoping phase, UK policymakers were particularly interested in places left behind by innovation, and the role of non-traditional innovation actors such as Further Education colleges in supporting broader equity and prosperity enabled by innovation. The experiment ideas we scoped clustered around two key themes supported by emerging literature: the importance of role models in shaping career aspirations ² and the need for increased exposure to ‘innovation capital’ ³. A number of ideas also focused on how to effectively deliver these interventions – specifically, how to adapt them for different contexts, such as reaching people from low socio-economic backgrounds or non-academic paths.

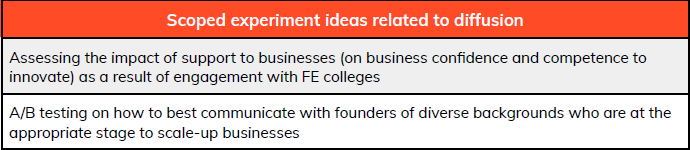

- Enabling the diffusion of innovation

A smaller cluster of ideas focused on the wider ecosystem: specifically, how skills and talent can support businesses that are experiencing skills shortages or looking to innovate. This theme highlights the critical need to connect training interventions (supply) directly with the needs of businesses (demand).

This scoping exercise was not just about generating lists, but about identifying where the ‘testable’ intersection of policy need and delivery capability lies, a process that ultimately led us to select two specific pilots for immediate implementation.

Within one year, this Programme achieved

8

Practitioner organisations

4

Policy Institutions

7

Researchers engaged

10+

Experiment ideas

3

Executive teams engaged

2

Pilot experiments delivered

Designing pilots to inform decision making

The two pilot experiments selected to be taken forward into implementation were with:

- Catalyst (Northern Ireland): Testing ‘Hello Possible’, a programme introducing adults to the Disciplined Entrepreneurship framework.

- East Kent Colleges (EKC) group: Testing ‘Think.Design.Do’, a new online toolkit being introduced for equipping vocational learners with design thinking skills.

We selected these partners and projects, because they presented an ideal combination of readiness and ambition. Both Catalyst and EKC Group had created interventions ready to address specific skills gaps, leadership teams committed to rigorous testing (including random assignment and new data collection), and timelines that aligned with our own. Crucially, both also shared a long-term ambition to scale these interventions to a level that could support a large-scale field experiment and viewed these pilots as an important first step in building the evidence base needed to justify and inform that expansion.

Building evaluation capacity

Before implementation began, we worked closely with Catalyst and EKC Group to develop logic chains connecting their inputs to key impacts and to identify rigorous, context-relevant outcome measures. This process acted as a valuable capacity-building exercise in its own right. IGL facilitated the integration of academic expertise, existing literature, and implementers’ on-the-ground insights to reach consensus on what was feasible. It allowed the organisations to think through robust data and evidence-based approaches, clarifying the thinking around the programmes themselves, whilst also demonstrating the need for flexibility to make these ‘real-world’ experiments take place. We received positive feedback that even where evidence was not generated to answer specific questions, the process of designing a potential experiment was inherently valuable.

Navigating the implementation challenges

Our primary goal was to test the feasibility for an experiment but the results illuminated a more fundamental challenge: the inherent difficulty of launching a new intervention in complex environments. We found that even with committed leadership, operational realities, such as curriculum pressures, limited delivery dates, and competing priorities for teachers, severely constrained uptake. This friction is primarily a delivery challenge but directly impacts on the potential viability of implementing an experiment, including practical considerations such as when and how to collect data.

Promising signs: early evidence of impact

Despite these implementation hurdles, the pilots generated promising evidence about the potential of the interventions:

- Catalyst: The Hello Possible pilot found that participants amongst those who received the training in Disciplined Entrepreneurship at the workshop benefited from greater confidence (56 times the odds of reporting higher confidence than the comparison group).

- EKC Group: Qualitative feedback indicated that learners responded positively to the ‘Think.Design.Do’ toolkit, reporting improved problem-solving skills and confidence. The process also provided EKC Group with actionable data to optimise the toolkit for wider rollout.

While implementation challenges meant we could not reach the sample sizes necessary for a full RCT in this phase, these findings provide ‘proof of concept’ to justify returning to these issues were it possible to secure the resources for a larger, fully powered evaluation.

Concluding Remarks

The Unlocking Innovative Potential (UIP) programme was designed to test feasibility, but its true value lay in revealing the structural preconditions for evidence-based policy.

We saw how experimentation is a tool for the introduction of a new initiative, not just evaluation. Small-scale pilots proved invaluable for resolving a wide range of uncertainties about interventions while limiting costs. They allowed partners to test content, identify operational friction, and refine their delivery models. This iterative approach builds the necessary foundation for scaling, ensuring that when full rollout happens, it is built more on evidence rather than assumption.

Looking specifically at lessons within the scope of the pilots, we encourage those interested to read the full reports from each of the pilot experiments. Together, each pilot highlighted the potential and motivation to use better data and evidence to inform pressing implementation questions, but also highlighted the difficulties in actioning large enough sample sizes to make more concrete claims on wider policy implications (in other contexts). Nonetheless, the process of setting up experimental cultures and procedures improved broader evidence-based decision making and showed policymakers that funded initiatives, if well-resourced, could embed this approach in the future.

Lessons outside of scope but that still informed a deeper understanding of policy area included the need to generate more on-the-ground evidence on how to implement programmes to unlock potential (moving past experiments that explore the what or who). Often, the target population (those most affected) is clear and ideas on how to support bringing these actors into the innovation ecosystem are there. We know that there is a role to change mindsets on who views themselves as an innovator and to equip these would-be innovators with the necessary skills to excel in innovation or entrepreneurship careers. On the other hand, there is also a need to equip a wider set of the population with innovation skills to support the diffusion of good ideas – to democratise innovation more broadly. Here the ideas scoped when we cast the net wide fell into these two categories: to unlock would-be innovators’ potential and to support diffusion of good ideas – connecting the micro to the macro.

There were also many lessons on how to set up experiments, incentives and constraints for different stakeholders (the needs of implementers versus researchers, for example, are very different). These insights might be considered to sit outside of the initial scope but provide IGL with useful signals on what we might do next. For example, the community of practice we set up to connect researchers and policymakers to the experiment ideas in development acted as a great vehicle to bring together these stakeholders. In hindsight, we might have better set up spaces for focused topic discussions based on the two broad policy areas we uncovered, to steer conversations and collaborations towards impact. Impact for us continues to be setting up more policy-relevant experiments, to both influence experimental culture and to increase the chances for wider experiments. We see, as a result of this Programme, a need for both, whilst recognising that formative research might be something that needs to be responsible for longer, before considering the role of academic expert researchers.

Finally, going forward, IGL remains committed to setting the ground for research on the lost innovative potential in OECD countries, and to bring together thinkers and actors key to sharing evidence on this topic globally. Setting field experiments forms part of this work, but alongside it, the formative research that drives policy-relevant research and the convening role necessary to make sure good ideas are shared as widely as possible.

Looking ahead, we need to move beyond simply asking for ‘more evidence,’ as our experience highlights that generating it is inherently difficult without the right structural conditions. The friction we encountered in these pilots demonstrates that rigorous evaluation cannot exist in a vacuum; it requires more than just willingness from delivery partners. Therefore, we call on policymakers and funders to consider approaches that support implementation and research in tandem. This means aligning delivery and evaluation objectives from the start and ideally resourcing the whole system, to help ensure that local pilots are robust enough to answer national strategic questions

If you are interested in further information on IGL partnerships or collaboration on this topic, get in touch with our team at [email protected]

Resources

Footnotes

- Alex Bell & Raj Chetty & Xavier Jaravel & Neviana Petkova & John Van Reenen, 2017. “Who becomes an inventor in America? The importance of exposure to innovation,” CEP Discussion Papers dp1519, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE;

Madeleine Gabriel & Juliet Ollard & Nancy Wilkinson, 2018. “Opportunity Lost: How inventive potential is squandered and what to do about it,” 10 December 2018, Nesta;

Karin Hoisl & Hans Christian Kongsted & Myriam Mariani, 2023. “Lost Marie Curies: Parental Impact on the Probability of Becoming an Inventor,” Management Science 69(3):1714-1738;

Elias Einiö & Josh Feng & Xavier Jaravel, 2019. “Social Push and the Direction of Innovation,” SSRN Electronic Journal, posted May 29 2019, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3383703. - Laura Bechthold & Laura Rosendahl Huber, 2018. “Yes, I Can! – A Field Experiment on Female Role Model Effects in Entrepreneurship,” Academy of Management Proceedings 78th Annual Meeting (Chicago), doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2018.209;

Ghada Barsoum & Bruno Crépon & Drew Gardiner & Bastien Michel & William Parienté, 2021. “Evaluating the Impact of Entrepreneurship Edutainment in Egypt: An Experimental Approach,” Economica 89(353):82‑109, doi:10.1111/ecca.12391;

Thomas Breda & Julien Grenet & Marion Monnet & Clémentine Van Effenterre, 2020. “Do Female Role Models Reduce the Gender Gap in Science? Evidence from French High Schools,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 13163, IZA Institute of Labor Economics (posted April 27 2020; revised December 10 2025), doi:10.2139/ssrn.3584926. - Madeleine Gabriel & Juliet Ollard & Nancy Wilkinson, 2018. “Opportunity Lost: How inventive potential is squandered and what to do about it,” 10 December 2018, Nesta;

Alex Glennie & Adrian Johnston & Robyn Klingler‑Vidra, 2025. “We Need a Better Framework for Measuring Inclusive Innovation Efforts,” Global Policy Journal (blog post, 16 May 2025).